In South Africa, upon completing school, you were automatically drafted to the army for nine months, provided you were deemed fit for service. The fitness test comprised of gathering a large number of young men in a gymnasium, where they were stripped to their under shorts and made to wait in a queue until it was their turn to be examined by the doctor.

The examination itself was arbitrary, puerile, and consisted mainly of colour vision tests, touching your toes and the infamous fondling of the crown jewels while coughing to the command of the medical examiner. I could never figure out what they were looking for and how it would affect my performance in defeating the enemy.

About four weeks after the test, I was informed by registered mail that I had been drafted to the Natal Field Artillery, and furnished with the necessary documents and train ticket.

Thus it was, that in my tender youth, barely three weeks out of school, I found myself with about 250 equally bewildered lads on a train station platform. There was a huge crowd of people comprised of the draftees, girlfriends, parents, siblings, relatives and friends. The tears, long faces, hugs, kisses, and back-patting would have done justice to a Hollywood movie depicting soldiers leaving for a hostile front where the mortality was atrociously high.

Oh yes, I was part of the soap opera. I, too, had a girl friend, and had bought her a little gold charm in the hope that she would treasure it and wear it close to her heart while remaining faithful. My father stood stoically, trying to be the proud, stern patriarch, and offering sober advice about manly conduct, family values and tradition. My mother was a nervous bag of hysterical chatter and kept trying to get between me and my girlfriend, who was theatrically shedding large crocodile tears and had me convinced that she would soon be pulling out her hair in a display of tortured anguish.

The conductor’s whistle heralded the end of the chaotic gathering. There was a last minute clamber onto the train, young lads leaning out of the windows, engaged in holding, hugging, kissing and, for the lucky ones, a last intimate little fondle. The moment the train had cleared the station, the transformation among the draftees was instantaneous. None of us wanted to be associated with our recent performances. Instead, we had transmuted into jocks, each trying to outdo the other in our display of manly bravado.

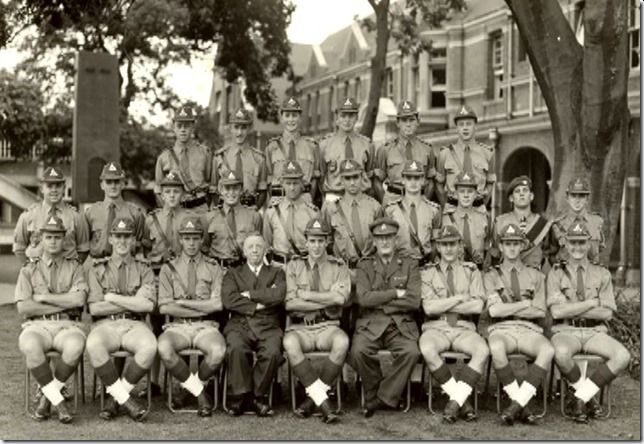

We arrived at the little town of Potchefstroom, whose main industry was to cater to the large military camp. The first six weeks was devoted to the complete annihilation of the draftee’s self esteem, thereby transforming one into an automated human being so that you reacted to a command without thinking. The usual day started at 5:30am with a one hour run, followed by breakfast, cleaning of the barracks, drilling and marching, then lunch and more of the same until supper time. After supper, it was punishment drill for those who earned a detention for some minor or imaginary infraction.

The military seemed intent on reshaping the way we thought, acted and responded. The slightest spark of defiance or individual expression was enough to send the Bombardiers (instructors usually of the rank of corporal or sergeant) into a frenzy that resulted in individual punishment or, worse yet, punishing the whole platoon for the alleged infraction of one person. The system worked. Each barrack housed one platoon and the solidarity amongst the men was unquestionably tempered by the universal desire to stay unnoticed and out of trouble.

Every Saturday morning, the Commanding Officer’s (CO’s) inspection of the barracks was the featured event. The panic began after supper on Friday evening. Everything had to be spotless, dead straight, ironed, polished, and in its exact preordained place. The slightest violation resulted in the most draconian punishment for the whole platoon.

The barrack split itself up into groups. Whilst some cleaned windows, others wiped down walls, or polished floors. Beds were made so that the sheets were all in an exact line and the edges ironed so that they looked sharp and crisp. There were two irons to a barrack and the most proficient ironers would tend to the shirts, pants and sheets. Sleep was not an option, although around 3:00am most of the platoon could be found taking a nap on the floor. (Beds had already been made and were without question out of bounds.)

No one had breakfast Saturday morning. The frenzy reached a feverish pitch. The floors were polished and wiped with wet cloths to make sure that there was absolutely no dust. We even had to dress a “very sensitive” six foot six lad that had suffered terribly from tormented nerves and was reduced to a whimpering mass of uselessness. Now, the actual inspection was a true Hollywood spectacular that would make the movie Full Metal Jacket pale in comparison. The sergeant would walk in, call the troops to attention, and the CO would walk in with swagger stick. Each individual would be scrutinized from head to toe. Just when you thought you had passed the test, the CO would double back and theatrically re-scrutinize you, thus rendering your bowels to a liquid mass. Finally, the coup de grâce.

Just before the final judgment, he would take the cap off the last man and toss it like a Frisbee under one row of beds to see if it picked up any lint or dust. I was never able to fathom why the army believed a fighting brigade could be defeated due to the presence of some lint on a cap.

Those first three months were very intense, and for the first time I blessed my parents for having sent me to boarding school, where the basic skills of survival under tyranny were learned at an earlier age. Witnessing the migration from the privileged and comfortable upbringing of most of the draftees, to the spartan and rough existence of a boot camp, was to witness an awesome transformation in social and cultural norms.

Finally, three months of intensive training was over. I was trained as an Observation Post Radio Operator, and quite happy with this until I learned that the life expectancy of such a position in wartime conditions was less three minutes. Crocodile Tears sent me a “Dear John” letter, and I was shipped to Bethlehem in the Orange Free state, which is the equivalent of remote Saskatchewan.

Not long after arriving in Bethlehem, a small contingent of men, including myself, were sent to perform guard duty at an open air storage facility in Pretoria. This storage dump was on the side of a steep hill overlooking the Pretoria Central Prison, which processed all the executions in South Africa. If that was not macabre enough, the hill was the scene of the worst war time accident in South African history. On the hill was a munitions assembly plant with earth bunkers built around little block houses. Apparently, there had been an accident, and some three hundred odd munitions employees never knew what hit them. The road from the bottom to the top switched back several times, and there were numerous crosses and memorials for many of the loved ones that had met their Maker on that fateful day. The local military personnel took delight in regaling us with horrific stories, embellishing on the gore of this tragedy, and warning us about the ghosts that roamed the hill.

Guard duty was four hours on and eight hours off, for twenty four hours a day, seven days a week. There were approximately ten specific locations that were manned with guards in this complex. The most notorious was right at the top of the hill, and was known as “Sadie’s Dump”. It consisted of a huge storage shed with an opening that faced the city down slope of the hill. The little tarmac road came all the way to this opening, and there was a generous enough space in front for a truck to reverse make a U-turn. Sadie’s was the last drop-off point in the guard duty circuit, and a long way from the guard barracks. There was a memorial to Sadie at the last switchback to the dump.

Apparently, some of her remains had been found there, and her troubled spirit was known to roam the hill. Rationally, of course, I knew that was absurd. Even more ludicrous was the assertion by some that she was looking for a body to inhabit.

On the surface, we all laughed and made light of these gory tales, but when you are on the graveyard shift from midnight to four in the morning, it’s not quite so funny. There was a particular event that, even today as I write this, makes the hairs on the back of my neck rise, and little shudders run through my body.

I had drawn the graveyard shift with a fellow we called Rat. He was slightly built with a long thin nose on an equally long, thin and freckled face, with a small mouth and little round dark eyes. Rat was not a great conversationalist, and he preferred to read his comics.

It was about an hour and a half into the shift, a proverbial dark night with not a breath of wind. The city below us was asleep and quiet. There were four lights on for the entire complex – two at the entrance where we were located, and another two towards the back of the shed. Inside were large crates neatly stacked in long rows. Rat was sitting inside the building on a seat he had fashioned out of pallets, reading his comics. I was also inside the building, about thirty feet away from Rat, with my back to the entrance, smoking a cigarette.

We both heard it at the same time. Rapid footsteps on tarmac gravel coming towards us. There was enough light spilling out of the building to illuminate the area in front and a portion of the road. In a fraction of a second we were both out of the building with rifles at the ready prepared to challenge who ever it was. There was no one. We looked at each other for confirmation that we had heard something, shrugged and went back to reading and smoking. Then the lights flickered once and went out at about the same time as we heard a loud crash, followed by another rush of footsteps, then total silence in the pitch black night.

To say that I was terrified would be a gross understatement. Every cliché pertaining to terror was applicable for the situation I found myself in at that moment. I am sure that the lights were only out for a few seconds, but it felt like ages. Then there was a flicker and the lights were back. But Rat was gone. Terror now had a companion – panic. What had happened to the fellow? My mouth was dry, my heart was still in my throat, and I was sure any sudden movement would result in loss of bowel control.

In my best controlled stage whisper, I called his name. No answer. I called a little louder. Still no answer. It is amazing how many thoughts both rational and irrational are able to cram your brain in the space of a few micro seconds, and Sadie’s Curse was definitely the most predominant. I ventured another louder, “Rat!” This time a faint voice answered, “Yes.” He was atop one of the crates at least eight feet up. How he got there I do not know and, neither did he. His rifle was still on the pallet where he had been sitting. The backrest, which was a larger pallet, had fallen off the stack and was on the ground. That was probably the crash I heard, caused, no doubt, by Rat leaping off his perch the moment the lights went out.

I surmised that the sound of that crash had literally galvanized him into a superhuman leap. The most amazing part of this Olympian feat was that it was apparently done effortlessly and in complete darkness.

Whatever had occurred that night could in part be logically explained, with the exception of the first set of footsteps and Rat’s superhuman leap. I served several more stints at Sadie’s Dump, but fortunately none were the graveyard shift. Rat, on the other hand, at the risk of being sent to detention barracks, absolutely refused to do either a day or night shift there.

It was a relief to have completed that duty and be returned to Bethlehem.